EPIPHANIES FOR EVERYBODY

Why Effective agile Increases Perception of Uncertainty

How agile Ways of Working Cope With Uncertainty

(NB: A version of this article was previously published here. This version has been further edited and refined.)

The most common complaint I hear from frustrated senior leaders adopting agile ways of working is, “I just want to know when it’s going to be done. I used to get that, before agile. Why is there so much more uncertainty now?”

I have good and bad news. The good news is there is less uncertainty now than there used to be. The bad news is the uncertainty that exists is out in the open and must be dealt with, adding yet another thing to the unending list of things on their plates.

Forcing the uncertainty into the open isn’t all bad news, however. It comes with opportunities for those who are prepared. As long as the uncertainty iswas hidden, there iswas no way to understand, identify, or resolve it. But now that it’s visible to everybody, there are ways to cope.

There are 2 reasons why the uncertainty feels different now: the first is how agile ways of working deal with uncertainty; the second is how previous ways of working did not.

Mastering Uncertainty with agile Ways of Working

Agile ways of working excel in exposing uncertainty. They proactively bring uncertainties to light and reduce them, ensuring stakeholders are always in the loop to avoid surprises. This approach empowers teams to openly address uncertainties and promptly inform relevant parties. As a result, senior leaders gain a clearer understanding of existing uncertainties at the same time as their teams.

Years ago, I worked with a team that was implementing a big change to their software. The uncertainty around implementation methods and timelines was evident. Facing an uncertain finish date was challenging for the business. To tackle this, we refined our approach.

For each unit of work, we sought maximum clarity and kept tasks small, limiting them to two-day durations. But sometimes, no matter how we sliced it, some work came out bigger than we thought reasonable. Whenever a task seemed unreasonably large, we found that it indicated excessive uncertainty.

Our strategy involved creating new work specifically focused on understanding the unknowns and associated risks. Investing two days in risk comprehension often led to:

More effectively completing the original work,

Generating new, better formulated work, or

Revising our strategy based on new insights.

Focusing on reducing uncertainty wherever we found it enabled us to continually expose, communicate, and reduce uncertainty. Initially, progress was slow due to the many unknowns, but as we progressed, our pace accelerated, which lead to exceeding progress expectations, ultimately resulting in both high customer satisfaction, and high quality software. Because we addressed uncertainty up front, we avoided any surprises at the end of the project that would have created significant delays.

When teams confront uncertainty head-on, it might seem like uncertainty is increasing, but in reality, it's being made visible and steadily reduced. One of the negative side effects of this approach is falling prey to one of the most common cognitive biases, which encourages us to put too much focus on things we encounter frequently (known as availability bias).

For example, despite data showing the world has become safer over the past 40 years, constant exposure to crime and violence in the news creates an impression of increased danger. Similarly, regular engagement with uncertainty can skew leaders' perceptions of its extent. Adjusting expectations with this understanding helps leaders appreciate the true impact of addressing uncertainty in our work.

______

A Traditional Approach to Uncertainty

In software projects, uncertainty is a given. Software is more about design than delivery. Constantly or incrementally learning what customers want and providing it is an inherently uncertain and creative act. But when we set an entire project's scope, budget, and timeline in advance, before creating anything, we don't leave room for unknowns to be exposed and addressed. This rigidity leads to problems, as leaders often treat "we didn't know" as an excuse, which discourages open discussions and learning.

Planning up front creates a false sense of control. Because leaders expect predictability and certainty, teams project it, even though they aren't. Everyone collectively plays along with this fiction, avoiding the real issues. Everybody knows it's a fiction, but it's a comfortable one, and the rules are clear.

The impact of The Old when adopting The New

In reality, projects weren't always delivered on time, within budget, or fully scoped. But when undergoing change, we tend to think about the familiar more fondly. Adopting agile methods, which are new and different, triggers discomfort due to our preference for the familiar. That often manifests in rose-tinted reflections on that past, where we romanticize what came before precisely because of how it’s in contrast to what’s happening now.

It's easier to criticize new approaches than to honestly evaluate our past experiences.

At its core, software development is unpredictable. When leaders demand certainty from tech teams on sizeable projects, it highlights a lack of understanding about the inherent variability in this field. It also signals that acknowledging these uncertainties isn't acceptable. This puts teams in a tough spot, leading them to withhold the truth. As a result, everyone — the team, the leaders, and the business — suffers.

Mitigating Uncertainty

There are several practical steps leaders can take to mitigate the uncertainty of both working in new ways and software development.

Don’t Ask Teams To Multitask

There’s something satisfying about multitasking. It encourages us to think we’re making the best use of our time, it keeps us challenged, and it feels like we’re making progress. Unfortunately, despite the satisfaction, multitasking is horribly ineffective and inefficient. By its nature, multitasking means working simultaneously on multiple things, which slows down the first thing on the list.

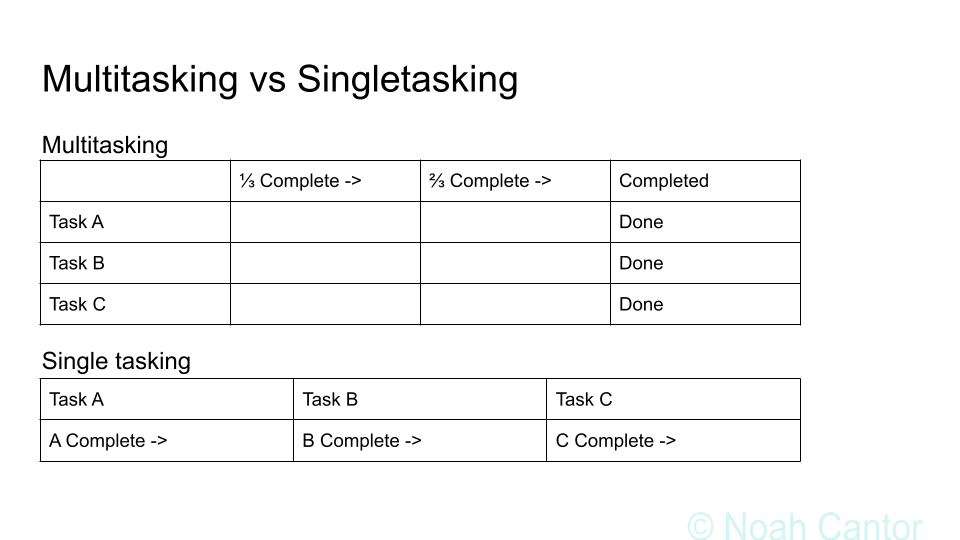

Imagine you have 3 things to do. Each one will take a week to complete. Multitasking means that each task will be completed in 3 weeks. Nobody will get what they want until 3 weeks have passed. Single-tasking, on the other hand, means that at the end of the first week, something is delivered. Somebody is happy. At the end of the second week, another thing is delivered, and another person is happy. At the end of the third week, everything has been delivered. Only one person has had to wait 3 weeks to get what they want. The first delivery has been done for 2 weeks, and the second has been done for 1 week. In other words, single-tasking has effectively saved 3 weeks. Multitasking wastes time! That doesn't even account for the additional time lost by context switching.

Identify & Tackle Uncertainty

Shift focus away from timelines by asking questions that help expose uncertainty. Instead of fixating on deadlines, ask questions that uncover uncertainties. For instance, inquire about the team's confidence in getting a piece of work done. Rather than asking, "When will it be done?" and leaving it at that, ask "How confident are you?" Then, probe deeper to surface additional uncertainty by asking, "What would your timeline be for a 95% confidence level?" Lastly, identify the biggest uncertainties and discuss ways to reduce them.

Shift the focus from rigid timelines to managing the valuable yet variable aspects of the work.

Reward Openness

There’s a level of vulnerability required to admit ignorance. In order for teams to be able to learn from each other, they have to be willing to admit what they don’t know. In order for them to be comfortable sharing their uncertainty (their areas of ignorance), they need to understand that ignorance is never punished. Admitting ignorance is the first step to learning.

The team should encourage people to work on things they don’t understand, and pull skills and knowledge from people that do understand it. When they share they don’t know something with you, thank them. When something goes wrong, treat it as an opportunity to learn and grow, not a time to blame. In every way, encourage people to be more open, trusting, and vulnerable.

Reinforce Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration

Uncertainty in software projects isn't just about the nature of the work; it's also about team dynamics. Often, key knowledge is held by a single person, creating uncertainty around their availability. What happens if they fall ill or leave? Typically, those with the most knowledge not only get the most engaging tasks but also influence work distribution.

To combat this, shift the focus from rewarding individual knowledge holders to encouraging knowledge sharing. Celebrate when crucial information is shared, like during brown bag sessions. Encourage team members to select their tasks and involve others as needed. Avoid rushing to complete tasks, which can lead to knowledge hoarding. Instead, aim for teamwork, building and strengthening connections along the way.

Promote practices like pair and mob programming and collective problem-solving. Adjust promotion criteria to value teamwork, knowledge sharing, openness, and teaching. Every step towards this new approach will contribute to improving the overall process.

Encourage The Team to Involve Leadership

Encouraging your team to involve leadership is crucial. Often, teams hesitate to share bad news with leadership due to fear of negative reactions. They might sugarcoat issues or hope they go unnoticed. However, reacting poorly to bad news only ensures you remain in the dark about real problems.

Reducing uncertainty means confronting it. It's vital for your team to feel comfortable sharing news about setbacks or changes, knowing they'll receive constructive support. And that you will constructively help them deal with it. This approach shouldn't just come from you but from all leadership peers. When working on customer-related projects, it's essential for software teams to collaborate with customer-facing teams, including their leaders. This involves openly discussing progress, challenges, and successes.

Conclusion

To achieve more predictable outcomes, leaders should focus on reducing uncertainty.

Stop multitasking requests,

identify and address areas of uncertainty,

promoting openness, knowledge sharing, and collaboration.

Encourage your team to bring up issues to leadership.

While they might not know the exact delivery time for a project, ensuring they're working on the right things in the best way possible is key. If needed, leaders can step in to reduce scope, resolve conflicts, or hire more staff for long-term benefits. This approach leads to better relationships, results, and a happier, more effective team.

Subscribe to my Newsletter

Copyright © 2026 Noah Cantor Ltd. All Rights Reserved.